By Anton Braholli

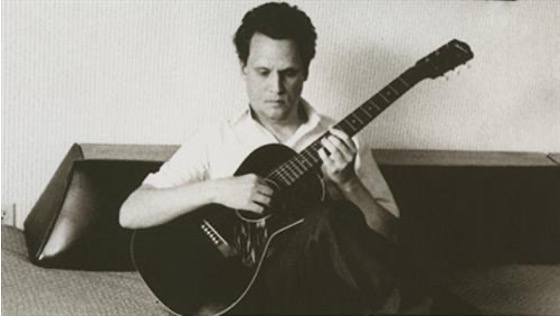

To understand the power of the album Benji (2014), here is a quick introduction to the path that led to it. Before Sun Kil Moon, there was Red House Painters, a band led by Mark Kozelek, whose music redefined slowcore in the 1990’s. They emerged from San Francisco and quickly developed a reputation for their slow and melancholic songs. Katy Song is one of their most well-known releases (reaching over 14 million listens on Spotify). Even from this track alone, Kozelek’s lyrics are poetic and direct.

After Red House Painters dissolved in the early 2000’s, Kozelek went under the new name Sun Kil Moon which was a play on the name of Korean boxer Moon Sung-kil. Through his 2003 single Carry Me Ohio and 14-minute song Duk Koo Kim, it became noticeable that Kozelek’s interest for memory and mortality were growing but still wrapped in traditional song structures. His lyrics have always been personal, but his earlier work was more metaphorical and polished with heavy focus on atmosphere and melancholic mood.

Over time, that approach to songwriting gave way to something messier and more journalistic, and so by the time his album Benji arrived in 2014, Kozelek had fully embraced a kind of hyper-realistic form of confessional poetry which abandoned metaphor almost entirely. Similarly, the instrumentals also followed this shift as Benji is built around loose acoustic guitars and minimal percussions which gives simplicity and gave Kozelek’s voice total control.

Carissa and Truck Driver’s Repetition of Tragedy

Comparing the opening track Carissa with the third Truck Driver, both songs seem to be narratively aligned to be true, and this is exactly Kozelek’s point: expose the tragedy through triviality. In Carissa, he recounts the sudden death of his cousin who died in a freak accident fire after a deodorant can was left in rubbish bin. Two songs later in Truck Driver, he tells an almost identical story about his uncle who had died in the exact same way. Even from the lyrics it is clear the Kozelek is laying bare the irrational repetition meaningless tragedy, he is not creating some poetic parallel.

“Carissa was thirty-five, you don’t just raise two kids and take out your trash and die” – Mark Kozelek (Carissa)

“He was working on a heater in the truck and the can blew, and it blew him down a hill, and it burned him through” – Mark Kozelek (Truck Driver)

The absurdist weight of these lines doesn’t necessarily come from the bizarre nature of the deaths but from Kozelek’s fixation on their senselessness. There is no villain or larger system to blame here, because in Benji, this is death: unpredictable and indifferent to narrative closure. What differentiates this from an ordinary story to an absurdist reckoning is Kozelek’s relentless need to make sense of it even though he knows he can’t, it’s just grief scattered in lyrics.

In Carissa, he tells the story of his second cousin’s troubled past of teenage pregnancy and her ordinary life as a nurse. No amount of storytelling restores meaning and this echoes through the lyrics: “I didn’t know her well at all, but it doesn’t mean that I wasn’t meant to find some poetry to make some sense of this”.

In Truck Driver, he repeats the same lyrical tone by listing his childhood memories juxtaposed with vivid descriptions of his uncle’s death: “In the winters, us kids would order Dominoes and watch Happy Days”/ “Third degree burns, a charred-up shovel near his hand…My uncle died a respected man”. Yet again, these are not metaphors, these are Kozelek’s desperate attempts to keep the person alive in memory as he is giving structure to something that by definition has none.

The whole album’s attitude corresponds closely to the Absurdist philosophy as the absurd arises from the confrontation between our desire for order and the world’s silent chaos. This is exactly what is happening with Kozelek’s writing as he tries to compute meaning from death but gets no answers. The repetition of two deaths, same cause, same end, it only heightens the futility. These songs reject the poetic or symbolic in favour of something more disturbing, this being the idea of raw casualty without relief. Kozelek’s act of telling these stories, even in their tangled, specific detail becomes its own response. If he can’t make meaning then maybe remembering is the best thing.

Violence and Memory in Pray for Newtown, Richard Ramirez Died Today of Natural Causes and Jim Wise:

In the most harrowing moments of Benji, Kozelek turns his attention outwards to the world, but not necessarily to escape the personal, instead he is showing the even larger scale of horror within societies have the same absurd logic that controls everything else. Through these songs, death appears without reason or pattern, whether it’s a mass shooting, a serial killer dying quietly in prison or a man killing his terminally ill wife out of mercy. These tragedies are real and continuing with his themes, Kozelek refuses to filter them through metaphor or moral commentary; by looking at the lyrics he catalogues them with a stream of consciousness.

“I was a Junior in high school when I turned the TV on/ James Huberty went to a restaurant and shot everyone up with a machine gun” – Mark Kozelek (Pray for Newtown)

“Bludgeoned people to death and wrote shit on their skin and left ‘em/ They finally got him, and he went to San Quentin” – Mark Kozelek (Richard Ramirez Died Today of Natural Causes)

“Jim Wise mercy killed his wife in her hospital at her bedside, and he put the gun to his head, and it jammed, and he didn’t die/ He went to trial all summer long and his eyes welled up when he told us how much she loved the backyard” – Mark Kozelek (Jim Wise)

Kozelek drags the sacred down to the level of the mundane once again, the deaths he documents aren’t elevated or symbolised in any traditional way. There seems to be a quiet horror in how violence blends into the background of everyday life, which isn’t a failure of empathy but more of an honest reflection of how we live in constant tragedy. Within Richard Ramirez, this is reinforced as Kozelek ends up on a tangent about his life and getting older whilst all this mayhem is happening in the world. Kozelek’s focus on specific details: someone’s tie, a dinner, a passing comment don’t clarify anything, instead it highlights how disproportionate our explanations are to the events themselves.

Maybe Pray for Newtown is an exception as it does show signs of sympathy, the song itself was written because of Kozelek receiving a letter from a fan about tragedy. This leads him to then start ranting about how tragedy occurs and how society seems to continue. Through his desperate singing throughout the song, it is quite clear he is telling the listener to remember that whilst they’re having fun and experiencing life, remember the tragedies that are unfolding without sense.

“When you’re gonna get married and you’re shopping around, take a moment to think about the families that lost so much in Newtown” – Mark Kozelek (Pray for Newtown)

The Existential Mess of Dogs:

Dogs is one of Benji’s most difficult songs because of its honesty. The song functions like a personal case file of Kozelek’s early sexual history, delivered with such specific lyricism that it becomes an existentialist view of romance within an album of tragedy. In Dogs, Kozelek does not hold back: from first kisses to threesomes and cheating…all laid out with no sense of poetic distance.

It reads as an awkward confession as the lyrics move chronologically but without resolution which creates a messy coming-of-age that reveals more about Kozelek’s own emotional damage than the people he is describing. By the end of the song, Kozelek embraces the absurd: “Nobody’s right, and nobody’s wrong/ It’s a complicated place, this planet we’re on”. The final verse lifts the song from a personal memoir to a more existential shrug, essentially saying that relationships are messy, instinctual, shaped by childhood, and ultimately outside our control.

What makes Dogs even more unnerving is the way it collides humour with the album’s tone. The metaphor “panting like a dog getting into someone” doesn’t glamourise desire, instead it degrades it by reducing sex to a biological impulse stripped of sentiment. Kozelek makes the listener complicit in the discomfort by being so unfiltered that it is disarming.

The song Dogs builds up the emotional weight of Benji by exposing another face of Kozelek’s emotional state. The humour sharpens the tension and reminds us that even in moments of intimacy or desire, absurdity still governs the narrative, and we are just stumbling through experiences we can’t fully make sense of.

The Strange but Comforting Conclusion of Benji:

Being one of the most known Sun Kil Moon projects, it is clear to see why it is so affective, especially with its trivialisation of tragedy. The horror is domestic: It’s a can in the rubbish, a tie at funeral, an album collection on a murder’s shelf. They are a debris of scraps leftover from lives suddenly gone and through all of it, Kozelek doesn’t attempt to find resolution, he simply documents what he knows. This is where the album brushes up against the absurd, in the face of death and chaos humans are wired to search for shape and meaning…but Benji doesn’t give into that instinct.

The whole album is Kozelek’s persistent narration into the void. If life is meaningless, he seems to suggest that memory might be our last protest to the unfree world. And this is the uncomfortable truth about Benji: it forces us to sit with the unresolved, like Kozelek, he is sharing these stories as an existential coping mechanism.

Perhaps Benji doesn’t offer catharsis because it knows better as it understands that honesty doesn’t always soothe, and so in this sense Benji isn’t just an album about death; it’s about the absurd task of remembering stories of this complicated mess of a planet we’re on.

Written by Anton Braholli

Leave a Reply