By Raquel Ruiz

Part Two of Sleeve Magazine x Raquel Ruiz’s Daughters Trilogy

The concept of the “perfect American daughter” has been something that has plagued my mind in middle school, but it began to worsen once I started working on my degree in college.

Both sides of my family are from Puerto Rico. Still, I would consider myself a no sabo kid because while the first few years of my life my parents spoke to me only in Spanish – I grew out of it and my parents stopped because once we moved to a suburban small town in New England; that is extremely Gilmore Girls coded to the point that all the PTO moms know everyone and will be gossiping at town hall meetings. One of my Titis when I was younger used to worry about my sister and me becoming white-washed and that we were straying away from our culture. At the age of 15, I don’t think I really understood what she meant. I knew that our town was 90% Caucasians, but it didn’t affect my viewpoint. Now I know that she wanted my sister and me to have a diverse friend group and connect with the Hispanic community and our Puerto Rican roots.

Again, when my family moved to New England, they began speaking Spanish to me less and less, as if it were something to be ashamed of. Then, once my sister was born, it was as if they had entirely given up on the ordeal. That was the first sign, the first realization where I felt less Puerto Rican. Each of us has role models, figures in our lives who show us what we should be because of where we are from. For my Mami, she told me how, after watching West Side Story as a child, she looked up to Natalie Wood because she thought she was Puerto Rican just like the character she played in WSS – Maria. But when my mami found out that Natalie Wood wasn’t Puerto Rican, that figure within the entertainment world she knew faded away. She told me that Rita Moreno was her only real representation growing up, and that while her love for her culture would always remain, her interests, like mine, focused on education because she realized that was the only thing that mattered in helping her family and securing her future livelihood.

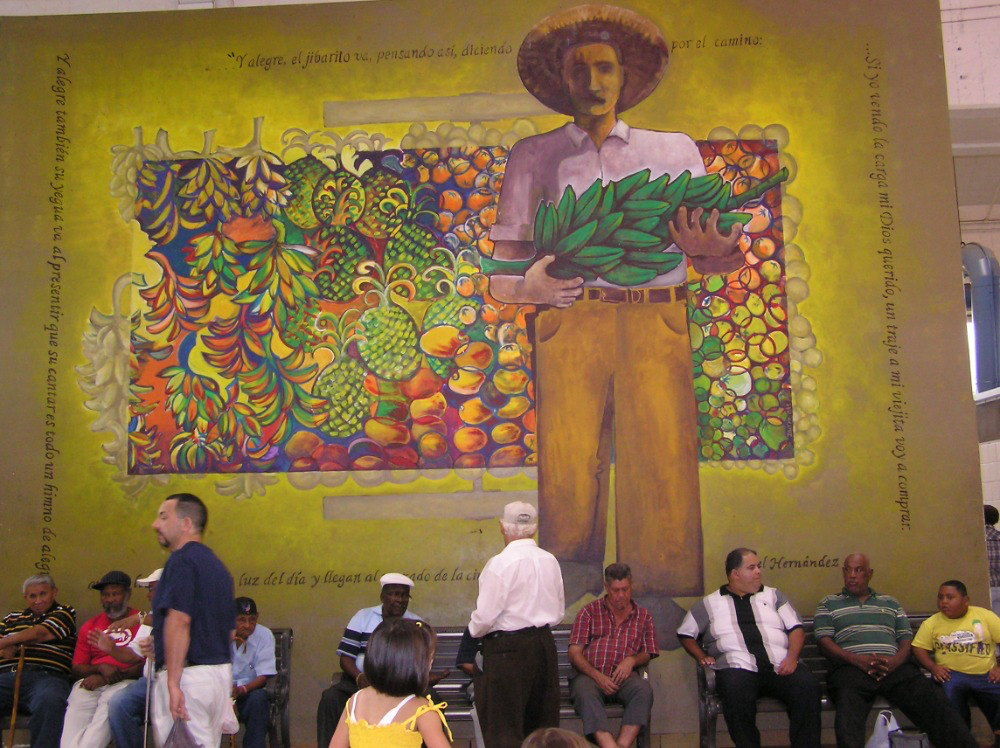

One of my earliest childhood memories is spending spring breaks in Puerto Rico, visiting both sides of my parents’ familia. We used to visit my Abuelito’s sister, who lived in the mountains of Utuado, overlooking a dairy farm, so we saw cows from her house balcony. Sometimes my Abuelito would drive us up higher in the hills to the old farm land where he grew up as a little boy. Being able to make those trips to Puerto Rico was my favorite thing to do because, since it was spring break, there were no expectations, no need to be a perfect daughter for your parents.

I built a mantra, a phrase of confidence for myself whenever I felt doubtful about trying something new or going somewhere.

My grandparents didn’t come from Puerto Rico to the U.S. for nothing. I need to make them proud. I need to do something positive with my life.

I was watching the Bad Bunny concert on Prime Video a few days ago and thought about how much my grandparents must miss their island, their casitas. Seeing the immense pride and love for Puerto Rico during that concert brings tears to my eyes. I think about how scared my Abuelito was to move to the States – leaving the only life he’s ever known.

Why was I nervous about losing a part of myself that will always remain in my bones just because I live in America? Though living here also brought new expectations that my parents upheld for my sister and me – it was vital that we succeeded and were perfect in whatever we did. While perfection may not seem attainable, I strived to achieve as close to perfection as possible in my education and grades. I’ll never forget when I received a grade of B+ in my pre-calculus class, and my dad told me to draft an email to my teacher asking for a retake because my grade was unacceptable.

Eventually, I became addicted to checking my grades, getting extra credit in my courses, and looking at my ranking in my class – I strived to be in the top 100. In the beginning, that drive came from wanting to please my parents. I lost interest in my hobbies because my sole focus was perfection. I attended a vocational school, and half of the students in my grade were highly competitive, aiming to be in the top 10 of the school. There was competitiveness, even as the valedictorian of the class, and while I didn’t achieve that status, the knowledge that I didn’t make it into the top 10 left me a bit disappointed. Some students had more advantages, including financial resources and opportunities, than I did to achieve those high grades. They had wealthy parents who could afford the best tutors that New England has to offer, allowing their children to gain admission to prestigious institutions like MIT or Harvard.

I interviewed one of my friends, Aleen, who is a second-generation immigrant in her household, and how moving to the U.S. affected her upbringing and how her parents raised them.

In this current day and age, there are many stereotypes perpetuated in the media about women of color. Growing up, did you ever try to break those norms and stereotypes? Whether it’s within your own family or social circle?

A: “I grew up in a Pakistani household in the U.S. – back in Pakistan, it was always that women were the housewives; they would do everything for the men. It was always a joint family system; the women were always catering to everyone else. My dad was more on the traditional household style, stereotypically placed in a certain box of what to do. While my mom really encouraged us to be independent, as men would, I adopted those traditional male roles, staying out late, going to college, and leaving the house. When it comes to stereotypes, Muslim women were always quiet and more reserved, and that was definitely a challenge for me. In middle school, my brown friends and I broke stereotypes that other people wouldn’t and weren’t afraid to allow ourselves to speak up and take space in our community.”

R: “That’s really beautiful – I’m not gonna cry. It’s imperative that whatever culture or community you are a part of, you put your mark on the world. At home or socially, to say this is who I am and that’s something you shouldn’t be afraid of. It’s something to embrace.”

What was your experience like growing up as the first or second generation in your family?

A: “Academically, there was an emphasis on completing the degree and making your own way. At the same time, there was a double standard to attending college, but staying with family so we could control what you’re doing and monitor your every move.”

R: “I was talking to one of my friends earlier this week, and they told me they didn’t feel like a virgin anymore in the ‘real world’ in the sense that they were able to do stuff that they were afraid of because they were home. Was there something that you felt like you broke out of a shell that your parents did or didn’t coddle you in?”

A: “100% percent. At first, there was a fear of experiencing too many things. I learned to be by myself, be alone, and it’s not a bad thing.”

R: “Was there any competitiveness with your generation between your cousins and yourself, like your grandparents saying you should’ve or shouldn’t go a certain route in your career, or what you should’ve done as a daughter in a Pakistani household?”

A: “Everyone had their own two cents on what you should do. They were so triggered by the fact that I was going to community college. They didn’t even give me a chance to defend my actions – I saved my family a lot of money.”

What rules did you have to follow in your family growing up?

A: “My dad wanted me to learn cooking at a young age. The rules are more like personality; you don’t always need to speak your mind. Things like being a daughter, not a son, not going out late, not always wanting to go out during the day, my dad is the most social person ever, and I’m asking him in my head ‘Where do you think I got this trait from? Like the apple didn’t fall far from the tree.”

R: I’ve definitely dealt with that a lot. My dad’s side of the family didn’t like the way we merged English with Spanish, and my Abuela used to tell my Mami that the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree. Incorporating English with Spanish made my sister and I being considered ‘no sabo kids’.”

Following up on that question, was there a need to be perfect at something in particular?

A: “Definitely, religion-wise, there were some things that my dad did following our religion and others that were suspicious. It felt like he was retracting his own word and being hypocritical within the religion. There was a need to be perfect and pressure to be a perfect muslim.”

Did you feel the need to “Americanize” yourself in any sort of way?

A: “It was a culture shock, a double standard to ‘Americanize’ yourself but still maintain your Pakistani roots and be present. When you’re with your family, you can code-switch some words in English and some words in Urdu. I had to immerse myself in American culture to be able to socialize and engage in more conversations. Once I came back home, my Pakistani community, my parents, and my friends did notice the American version of me.”

There has been a wave of immigrant daughters losing touch with their culture to fit in and to understand the topics that will be brought up when going out with their friends. You want to be a part of those conversations. I learned not to be embarrassed about listening to Spanish music and bachata boy bands, which were a part of my childhood. There is a fear that you won’t be liked because of the food you eat or the language you speak.

Even at 22 years old, I still hear conversations at work that suggest speaking Spanish at the workplace is unacceptable because people don’t understand what you’re saying. The double standard is crazy and unfair. Being able to reflect on my childhood and understanding the implications that come along with looking and sounding more American.

As a daughter of two Puerto Rican parents, I fear that my need to impress them will never go away, and within the Hispanic community, it’s vital to lift one another to follow your dreams and aspirations while remaining close to your family, and it seems out of touch to be so American. Immigrant households have different rules and regulations, which make those individual cultures unique, so why take away that cultural factor that makes you the person you are today? Will you allow your culture to influence and flow through you? Your ancestors, your culture, it’s burned into your DNA, your personality, and no matter how many times your family members criticize you for sounding American, you shouldn’t feel disassociated from your home.

At the end of the day, I’m grateful to be from Puerto Rico and be a daughter to my mother and father, who carry such pride and love for their island, and the influence of the Latino culture will always remain in me.

Leave a Reply