I’d been invited to a showing of clothes. This meant racks with hangers, spaced out well, and other decorative things in a room that must play host to three hours of considered walk-arounds. After this, the room empties, of people and things, and waits for the next time it is useful, functional, fashionable.

A bit like a trend, that’s where my head went.

I’d not been to a London Fashion Week event before, and I think I’ve struggled to digest it too, hence the delay between that week and the one that this is being published. Looking at and feeling the clothes, exclusively monochrome or muted in tone, their casual slackness coupled with a feathery eccentricity, had me feel that it was appealing to/enforcing its own idea of the bohemian. I’d have liked to have been fascinated by some craftsmanship and vision, rather than the way in which these clothes had such a simple premise and yet fell short of either feeling relevant or inspiring.

This may sound harsh, but when clothes are made to be simple and comfortable and good to live in, I cannot sit and write that for what they were (simple, comfortable, unremarkable) they deserved to be priced at upwards of £600 a piece. I think the key here is that I am not being pessimistic, or even virtuosic (I cannot sew nor design well), but that whatever it is that bohemian means, this chafed against the collection I was looking at here.

We’re always in a cycle of inheritance, we just shrug off certain aspects of a whole as we reinvent an item, belief or aesthetic of the past when fitting them to our present lives. This is true of the bohemian styles that have made their way back to the high-street. Blousy, flared and fringed clothing beset by gems, studs and strings, these are call backs and interpretations. But defining bohemian and bohemianism solely by the version of itself now, the one that has gained the most cultural currency as being Isabel Marant-ified and Chloe-girl’d, would be to slight and diminish its ancestral forms. I won’t pretend this is a comprehensive overview or education on all the many antecedent and current cultural clashes. Choosing a focus for this piece is a privilege and it is also a necessity to prevent rambling. My (loose) focus then, is where interpreting the bohemian – for the sake of “boho chic” lifestyle inspiration – can go wrong.

Chloé Winter 2025 Show https://www.chloe.com/en-us/fashionshow/winter-25.htm

When I said that these clothes did not have relevance, I broadly meant this: it is fundamentally skewed that living comfortably and well should come at impossible costs, and if this is the measure, then the vast majority of us are living terribly, and unfashionably at that. There is nothing liberating about forking out money you don’t have to wear clothes that you do not need, nor should they cost this much. This matters both on principle and on concept.

To invoke or play with bohemianism is to gesture to a historic artistic, literary, social and cultural body with reasons and codes of being attached to it. More than just romantic and revolutionary sensibilities, the bohemian has sometimes been an individual also prescribed the descriptor precariat. For all the secession from conventionality comes from an environmental and social context, but for some the urge is to rebel against one’s own bourgeois class and for others a perceived or ascribed distinction/difference is already embedded, embraced passionately and then expressed deliberately.

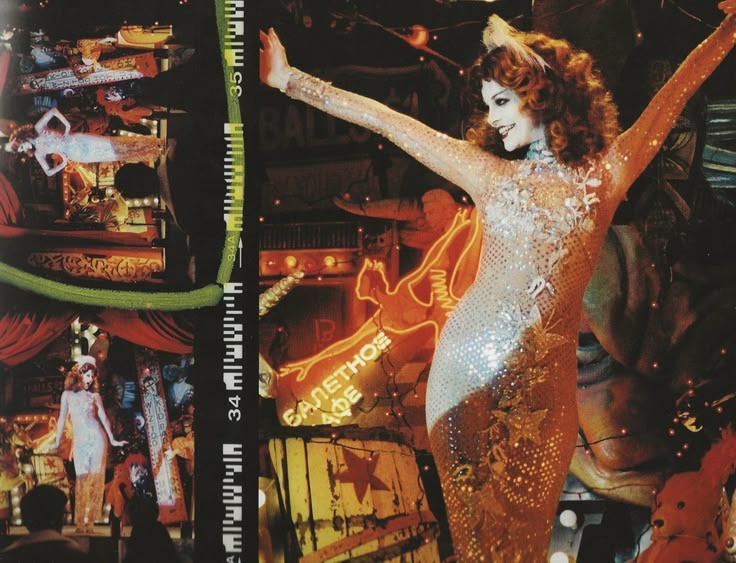

From Vanity Fair to Moulin Rouge, bohemian breakaways have been framed by poverty and starvation – whether material, ideological, emotional, social or otherwise. This topos feels forgotten now, the intentional construction of a boho-chic outfit divorced from a way of living, a way of coping, an attempt to construct a life of meaning.

Baz Luhrmann’s Moulin Rouge (2001)

As these thoughts paced their way round my head, the designer approached me and told me that ‘this collection is for the everyday woman to find beauty in her every day, in small habits like preparing lunch or reading’. It is fundamentally unsettling that such mundanities, of which not even everyone is guaranteed, are positioned as able to be made more beautiful by buying into an exclusionary, expensive vision of what it means to possess and live with elegance. It is contrary to the bohemian, who has often worked, who has got by through grit, who has experienced or been pushed to a fringe. I looked around and saw framed editorial photos propped up around the room featuring lone women lounging in or by large solitary houses on the coast, contrary to those who have often lived in close quarters who have also desired to find or create communality. Art, ideas and a life to be shared.

Unlike the isolated women looking down at their clothes in absorption, feeling satisfied with their new lot, the bohemian has historically gathered and collected their inventory of clothes, sometimes having attained items through personal association. A stranger’s gloves purchased from a second- hand vendor, a dress taken from the closet of an aged relative, a hat found abandoned on a bench.

Fashion through adoption, a routing out of accessible ways of coming into ownership.

In his essay “Bohemianism, the Cultural Turn of the Avantgarde, and Forgetting the Roma”, Mike Sell points out something very important and phrases it in a way that I cannot best.

‘The bohemian is fundamentally a creature of the modern moment and always something of a modernist. Regardless of where history is to be found, the bohemian assumes that authentic existence is historically conscious existence. To be bohemian is to be a memorialist’ (Sell, 2007)

Looking at our modern moment, I lack the space or will here to adequately stress the obvious, painful irony in the mass-consumption of mass-produced replications of items worn by artistic individualists, political collectivists, and counter-culturalists.

Is boho-chic memorialisation? Is it modernism? Is it even bohemian? I’d go on, but you get the gist.

References: Sell, M. (2007). Bohemianism, the Cultural Turn of the Avantgarde, and Forgetting the Roma. TDR, 51(2), 41-59.

Leave a Reply