By Anton Braholli

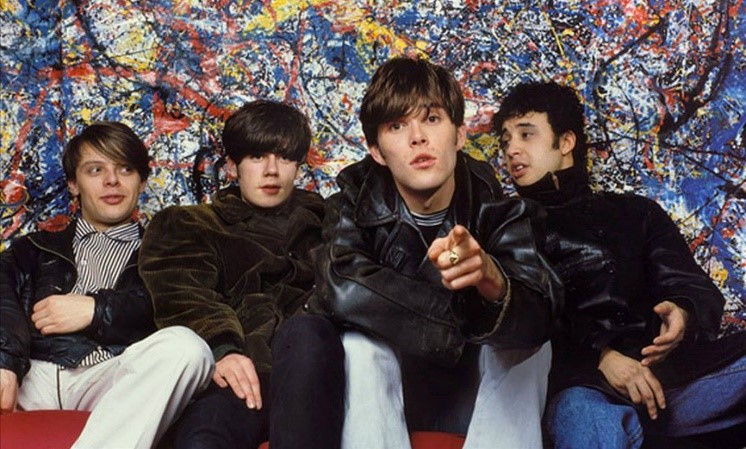

Emerging from Manchester in the late-1980’s, The Stone Roses became a defining part of the Madchester scene – a cultural movement where indie music became synonymous with dance rhythms and rave culture. Their music wasn’t just about sound but a broader statement on freedom and identity at a time when Britain was still reeling from a decade of political and economic tension under Margaret Thatcher’s government. Thatcherism brought in privatisation and increased social inequality which alienated large swathes of working-class Britain and fuelled a growing sense of disillusionment in much of the country’s youth.

Despite only releasing two albums, The Stone Roses quickly managed to capture their psychedelia and rebellion all within lyrics, album covers and pure attitude. Their ethos was chaotic, yet deliberate, which can be explained by their post-punk origins and the ‘Garage Flower’ period in the mid-1980’s. The difference between Garage Flower (1985) and their official debut album The Stone Roses (1989) is the clear abandonment of raw, punk-driven aggression in favour of a more melodic, psychedelic sound. Whilst these traits may have faded in a musical sense, they were still kept alive through their art and lyricism, giving the band one of the most applauded albums in British rock history.

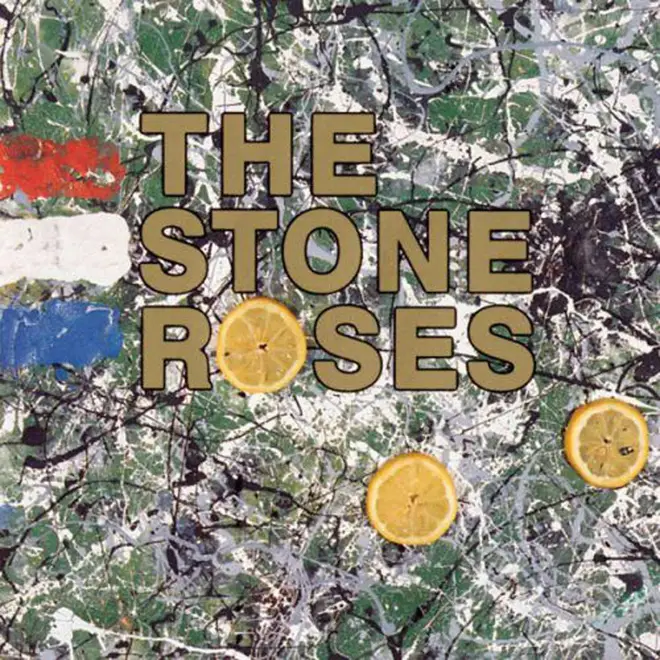

Taking one look at the cover, much can be deciphered. The drip-paint technique used by Squire for this cover was heavily inspired by Jackson Pollock’s work of the 1940 and 50’s. In 2008, for an interview on The Culture Show, Squire mentions the ‘buzz’ comes from the process of making art, not particularly the end piece, which sounds like his early punk roots showing through. This impulsiveness of Squire’s painting techniques mirrors Brown’s lyrical attitude throughout the album.

Brown’s lyrics are still punk in their own ways; it’s the way they are sung over Squire and Mani’s jangling melodies that had changed the band’s sound. Take the first song on the album, “I Wanna Be Adored.” In just under five minutes, The Stone Roses manage to capture a message about their experience in the music industry – “I don’t have to sell my soul, he’s already in me” repeats like a mantra, suggesting that Brown is acknowledging his choice in signing over to Silvertone in order to reach a larger audience, effectively wanting to be adored.

“Waterfall” could be a critique of Thatcherism and how the ex-prime minister wanted to be “free from the filth and the scum” – noting the heavy class divides in Britain during the ‘70s and ‘80s. Brown also taps into external forces, Britain had close relationships with the USA during the Cold War, and so the power of government control appears to Brown that the “American satellites won.” Despite America being a young country, Britain was being “whipped by the winds of the west.” and becoming disillusioned with its own society.

“Shoot You Down” and “Elizabeth My Dear” both carry similar themes of revolt and the killing of people in higher powers. Over the melody of “Scarborough Fair,” a traditional English strain, Brown creates a rebellious juxtaposition in the lyrics, explaining that the Queen’s death is inevitable, and the revolution will never stop. If people continue to resent the monarchy, its power will eventually dissolve. The idea of assassination seems extreme, but around 35 seconds into the song, the sound of a bullet is heard, symbolising that Brown’s “aim is true” and “message is clear.”

The most politically fuelled song from the album is “Bye Bye Badman,” which focuses on the Paris Riots in 1968. These student-led protests erupted over issues like class inequality, capitalism, and the rigidity of the French university system. To suppress the riots, police used CS-gas to maintain control. Ian Brown recalled being told by a man while hitchhiking across Europe that sucking on a lemon neutralized the effects of the gas. “Choke me, smoke the air” is Brown setting the scene of the hostile Parisian police, but the “citrus-sucking sunshine” will always defeat them; Brown wants them “black and blue.” Given this context, the iconic lemons on the cover gave the symbolism The Stone Roses were looking for. It gave them a meaningful connection to their youthful, rebellious attitude that they could bring over to Britain. Note that the red, white, and blue on the side of the cover could suggest the pride of Britain or a nod to the French flag as well.

Despite all of this, whilst having politically themed lyricism in their songs, The Stone Roses were never seen as a political band. In British culture, they are more synonymous with the Madchester scene, alongside the Happy Mondays and Inspiral Carpets: a movement often associated more with baggy clothes, hedonist values, and dance culture than serious political critique. This perception stuck, in part, because the band didn’t frame their work around protest in an overt way. Lyrically, they didn’t always get their messages across in the same direct fashion as bands like The Sex Pistols or The Clash, who built their identities around confrontation and clear opposition to establishment figures. Then again, those bands thrived within the punk genre, where anger and provocation were expected. The Stone Roses, by contrast, leaned into psychedelic rock, where meaning is often cloaked in metaphors. Their messages were there: ideas of disillusionment, class divide, anti-monarchy, and resistance but they were woven subtly into poetic lyricism and accompanied by jangly guitar riffs. It’s a different kind of rebellion, one less about shouting in the streets and more about creating a mood of defiance that seeps into the listener almost unconsciously.

This stylistic choice may explain why they never quite broke free from the Madchester label; their political commentary was often masked by their dreamy sounds. To many, they simply sounded like the soundtrack to an acid house party, rather than a reflection of anti-authoritarian sentiment. So this leaves the question: Can a band’s cultural impact truly be measured by its political message, or is their influence more shaped by the mood and energy they evoke through their music? The Stone Roses may not have screamed their dissent, but they embodied it, leaving a legacy that still resonates in British music today.

By Anton Braholli

Leave a Reply