Most people say they love fashion because they like clothes. They enjoy shopping, styling, and dressing well and that’s perfectly valid. Clothing is fun and whether consciously or not, a form of self-expression. But fashion as a cultural system goes far beyond fabrics and silhouettes. To say you “love fashion” isn’t just about enjoying what you wear it’s about being curious as to why we wear it. Fashion is shaped by history, identity, politics, law, economics, and social meaning. Long before a garment reaches the body or the runway.

Clothes are the result of fashion, not the definition of it.

Fashion has always mirrored the values and tensions of society. Throughout history, dress has communicated class divides, gender expectations, and cultural power. When Coco Chanel introduced relaxed jersey silhouettes and tailored suits for women in the early 20th century, she wasn’t simply creating a fresh look; she was responding to changing roles for women in society. Her clothes rejected restrictive corsets and the idea that femininity meant fragility. These designs were quiet acts of rebellion made wearable.

Coco Chanel modeling a Chanel suit on rue Faubourg Saint-Honoré in Paris, 1929. Private Collection. Creator: Sasha; (Alexander Stewart) (1892-1953)

Christian Dior’s post-WWII “New Look” did almost the opposite. After years of wartime austerity and masculine utility wear, Dior reintroduced exaggerated femininity with cinched waists, full skirts, and sculpted silhouettes. His designs celebrated beauty and luxury but also reflected a society eager to return to normalcy and structure. Fashion captured that shift more vividly than any textbook ever could.

“Pale tussore jacket hip-padded like a tea cosy; pleated jersey skirt.” Photographed by Serge Balkin, Vogue, April 1, 1947

Luxury brands continue to prove that fashion is about symbols, not just style. The iconic Louis Vuitton monogram, first designed to deter counterfeits, has evolved into a global emblem of status and aspiration. To carry an LV bag is to speak a shared visual language of class, sometimes proudly, sometimes ironically, sometimes critically.

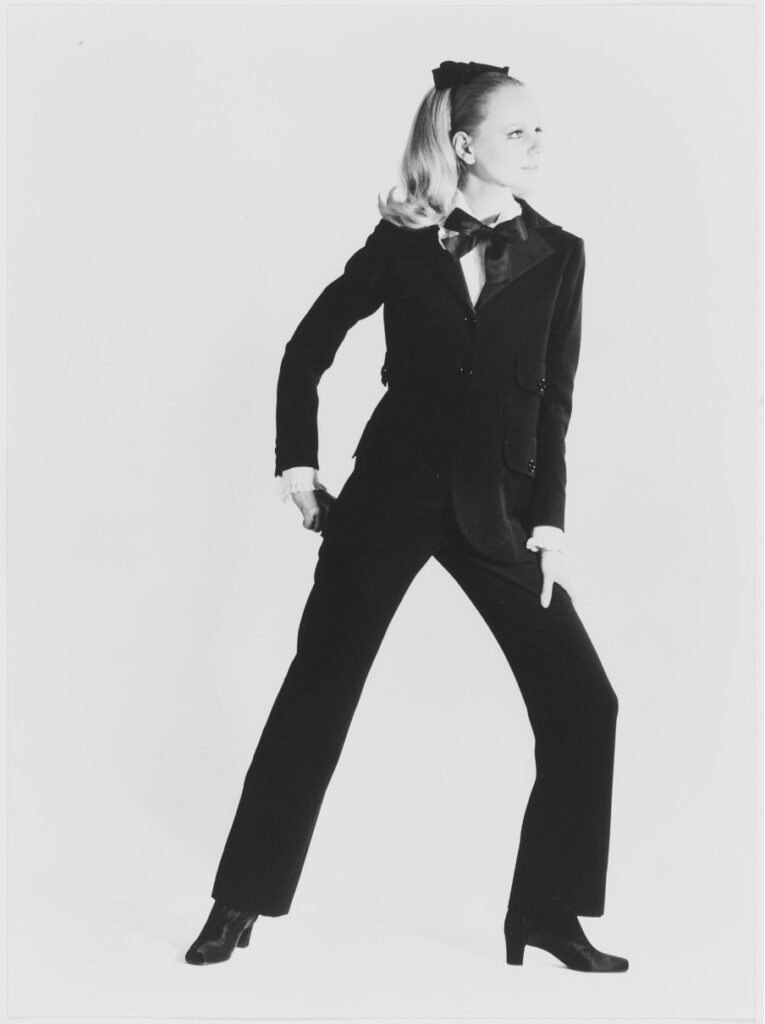

Yves Saint Laurent’s Le Smoking suit for women in 1966 pushed that symbolism further. A tuxedo for women wasn’t merely chic; it questioned why elegance had to be feminine. By adopting a traditionally masculine code of dress, Saint Laurent offered women a new form of power. The garment didn’t transform society alone, but it perfectly captured a social movement already in motion.

First tuxedo, worn by Ulla. Autumn-winter 1966 haute couture collection. Photograph by Gérard Pataa

Fashion also reflects the contradictions of our political and economic world. Under Demna Gvasalia, Balenciaga exposes and profits from the absurdity of modern consumerism. Oversized silhouettes, distressed sneakers, and intentionally “ugly” luxury mock the very system that buys them. Wearing Balenciaga becomes a kind of cultural wink: a critique of capitalism that still carries a four-figure price tag.

Comme des Garçons takes it one step further. Rei Kawakubo’s designs often distort, pad, ordeconstruct the body, blurring the line between garment and sculpture. By challenging traditional notions of beauty and perfection, she invites the question: Who decided what clothing should look like or who it should fit? Her work is less about dressing and more about thinking; philosophy disguised as fashion.

Comme des garçon “lumps and bumps” collection 1997. Sourced from Vogue

Together, these examples show that fashion doesn’t begin with a sketch or fabric choice it begins with culture.

Designers respond to everything that surrounds them:

*History shapes what feels relevant or outdated.

*Politics dictates what can be worn or banned.

*Law governs trademarks, labour and creative ownership.

*Economics fuels both luxury and fast-fashion exploitation.

*Identity and social rules decide who “should” wear what.

*Technology changes how clothing is made and shared.

The final garment becomes a kind of social code that we all, consciously or not, learn to read. Without realising it, we can distinguish between “professional” and “street,” rebellion and respectability, blending in and standing out. Fashion constructs these categories; clothing simply expresses them.

So, when someone says they “love fashion” because they love dressing nicely, that’s only the beginning. Style and personal taste matter, but they exist within a web of culture, commerce, and history that already set the parameters of what’s possible.

Fashion isn’t just the garment, it’s the context that gives the garment meaning.

Every outfit carries a story: Chanel’s liberation, Dior’s post-war idealism, Vuitton’s coded luxury, Saint Laurent’s gender defiance, Balenciaga’s capitalist critique, Kawakubo’s philosophical experimentation. Together they remind us that fashion is not simply about what we wear, but what our clothing says about the world that made it.

Leave a Reply