By Ella Holmes

Step off Piccadilly into the Royal Academy’s Annenberg Courtyard and in an instant, daily urban noise is replaced by something altogether more playful and quietly introspective. Five huge, inflatable orbs scrawled with questions such as ‘what do animals dream of?’ and ‘how much is a lot?’ are dotted on and around the venue; their scale and childlike script an invitation from artist Ryan Gander to set your cynicism aside, embrace curiosity, and linger in uncertainty, the precondition for conversation.

This scene is not just a preamble, but a declaration of intent for the 2025 Royal Academy Summer Exhibition, curated by visionary architect Farshid Moussavi OBE RA. The theme this year is ‘Dialogues’, and, as Moussavi sets out in her foreword, it is a necessary response to our era:

‘The Royal Academy Summer Exhibition 2025 is dedicated to the theme of ‘Dialogues’ and arises from the recognition that we are living through a time of increasing polarities – social, political, and cultural. In the face of such growing fragmentation, the aim of this year’s exhibition is not to dwell on division, but instead to be inspired by art’s capacity to forge dialogues about, and heighten our sensitivity towards, societal concerns such as ecology, survival, and the ways in which we live together.’

With these words, Moussavi frames the exhibition as an act of hope and creative resistance, insisting that conversation, in all its multifaceted forms, is not merely possible but vital in an era of division.

Inside the gallery, the anticlockwise route deliberately disorients in a disruption of expected rhythms, signalling a desire to reconsider how we move through and perceive art. Similarly different this year is the way in which sculpture and architecture are not confined to a cloistered room, instead threading through every space, engaging with art in a running dialogue of space and form.

Upon entering the Wohl Central Hall, visitors are immediately met by Alice Channer’s installation Body Shop. Inspired by the revelation that female ostrich feathers are used to remove dust particles between paint applications in the masculine environment of a car factory, Channer’s work illuminates the unexpected reliance of industrial processes on elements of the natural world. This striking intersection of nature and technology encapsulates the exhibition’s central theme of dialogue and symbiosis, priming viewers to discover the deeper meanings embedded within the works that follow. Following on from this room are ten spaces brimming with artistic interpretations of ‘Dialogues’, however, to avoid expending your time and energy, I have collated a group of standout pieces, rooms and ideas that embody the theme and feel of the exhibition this year.

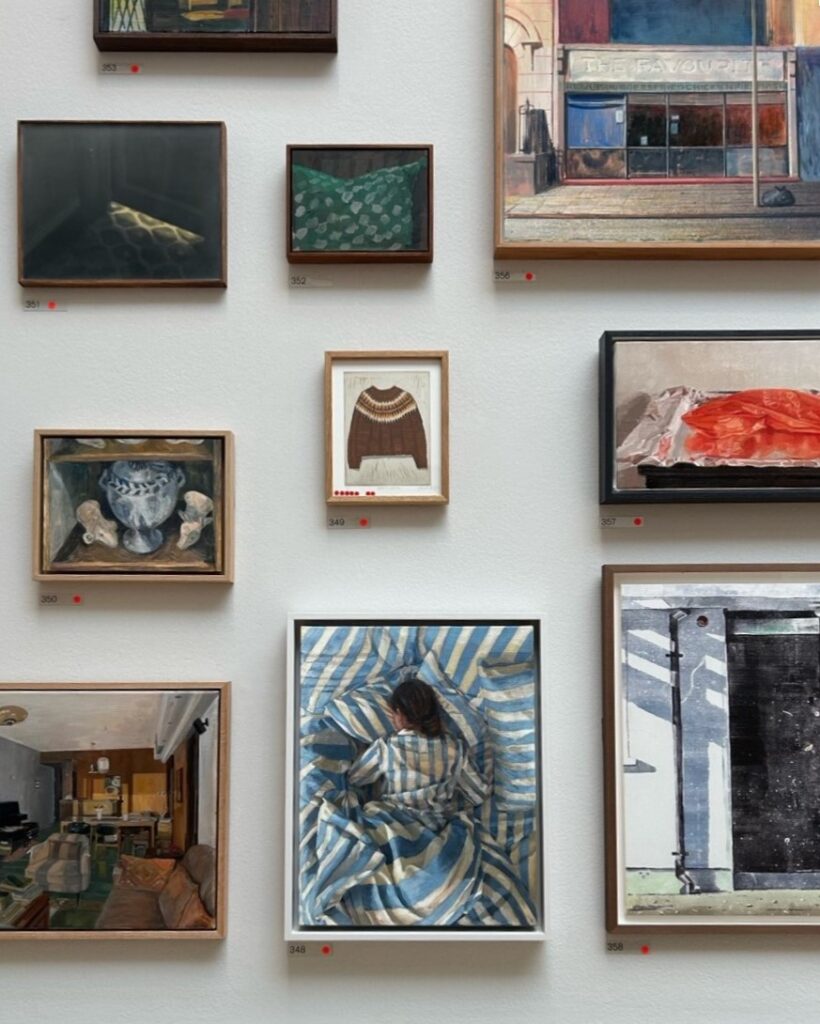

While wandering the exhibition, it is easy to be dazzled by the celebrated names, such as the magnetic presence of Tracey Emin’s The Crucifixion or the sharp wit of Grayson Perry’s Conversations With My Fellow Academicians. Yet, the true distinction of the Summer Exhibition lies in its openness to the unexpected. Here, the spotlight extends far beyond the household names to champion the everyday artist: A primary school teacher, an aunt, your local shopkeeper. The possibility that so many perspectives, amateur and professional, known and unknown, coexist within the same walls is itself an embodiment of dialogue, and this democratic spirit, unique to the Academy’s summer tradition, transforms the exhibition into an ongoing conversation, where every voice is invited.

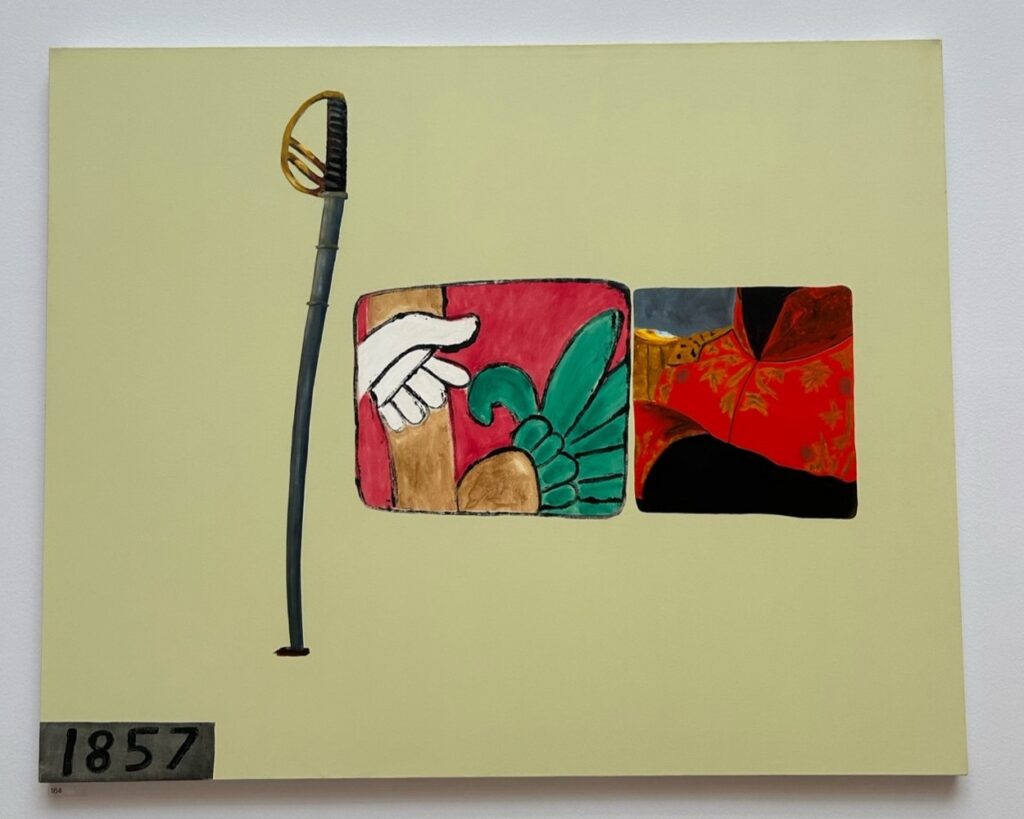

In the Lecture Room is Dexter Dalwood’s An Inadequate Painted History of Mexico X, which stirs complex conversation about the difference between local and global perspectives, and how history can misconstrue artistic representation. Within this exchange, viewers are invited to reflect on contested historical narratives, especially those surrounding Mexican identity and colonial history. Similarly, Barbara Walker’s two pieces Marking the Moment 12 and 13 continue the theme of historical misrepresentation, drawing on her signature practice of dialogue between past and present. By reinterpreting 17th century portrayals of societal figures and African pages, Walker challenges archaic narratives that have often erased Black presence and experience, while unsettling entrenched power structures.

Wandering further, Room IX boasts Steve Haigh’s Happy Feet, which thrives in its exploration of dance as a universal yet deeply personal language. The dancers are vessels of identity and joy, communicating themes of race and the human need for connection without words, making the work not only a visually arresting piece but a profound contribution to the exhibition.

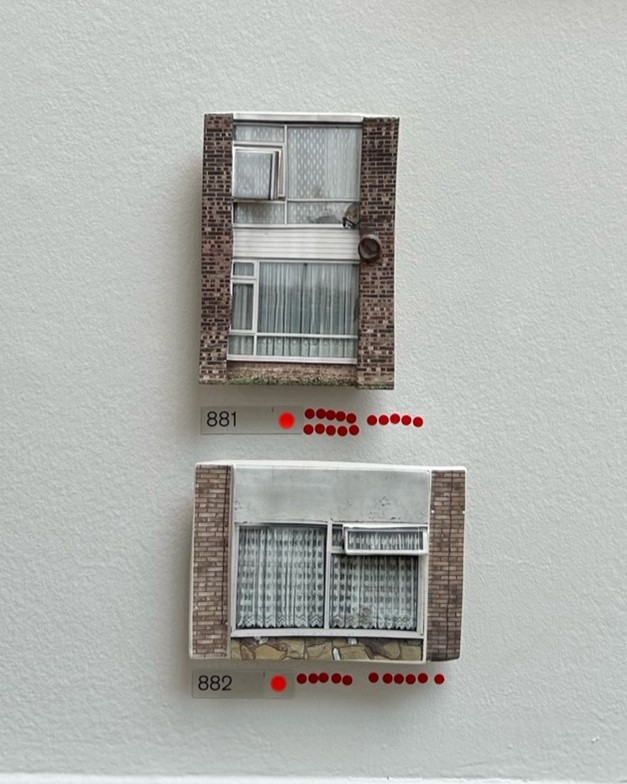

Sikelela Owen’s preference for familial, cross-generational scenes can be seen on all four walls of room VIII that she was tasked with curating, and Roger Adam’s quiet, sentimental piece Questions epitomises these snatches of nostalgic moments. In fact, the works are organised so beautifully that allowing your eyes to flit over the walls feels like stepping into someone’s living room filled with immortalised family moments. This is encapsulated by images such as I Don’t Want To Talk About It by Frances Featherstone, Living Room Scene by Shirley Lo and Snap Shot Memories (John) by Mark Surridge. Similar scenes of the beauty found in the mundane are celebrated in room V with Andy Seymour’s The Long Distance Gamer, Alice Mara’s ceramic windows, and Gillian Wearing’s Self-Portrait (Festival).

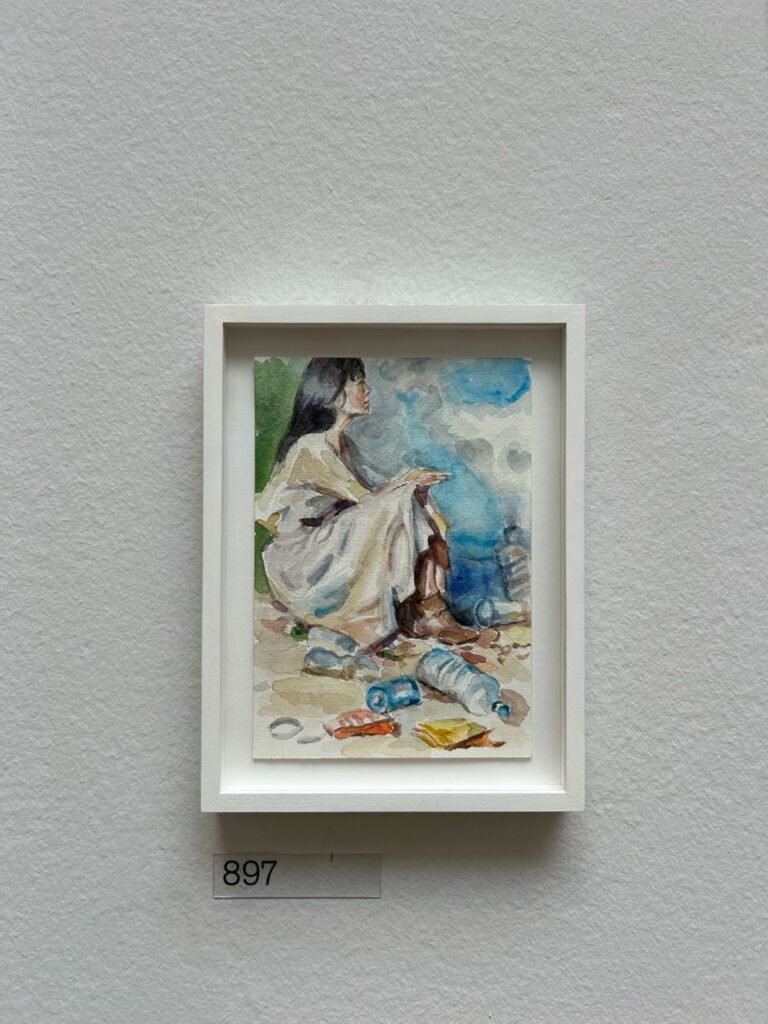

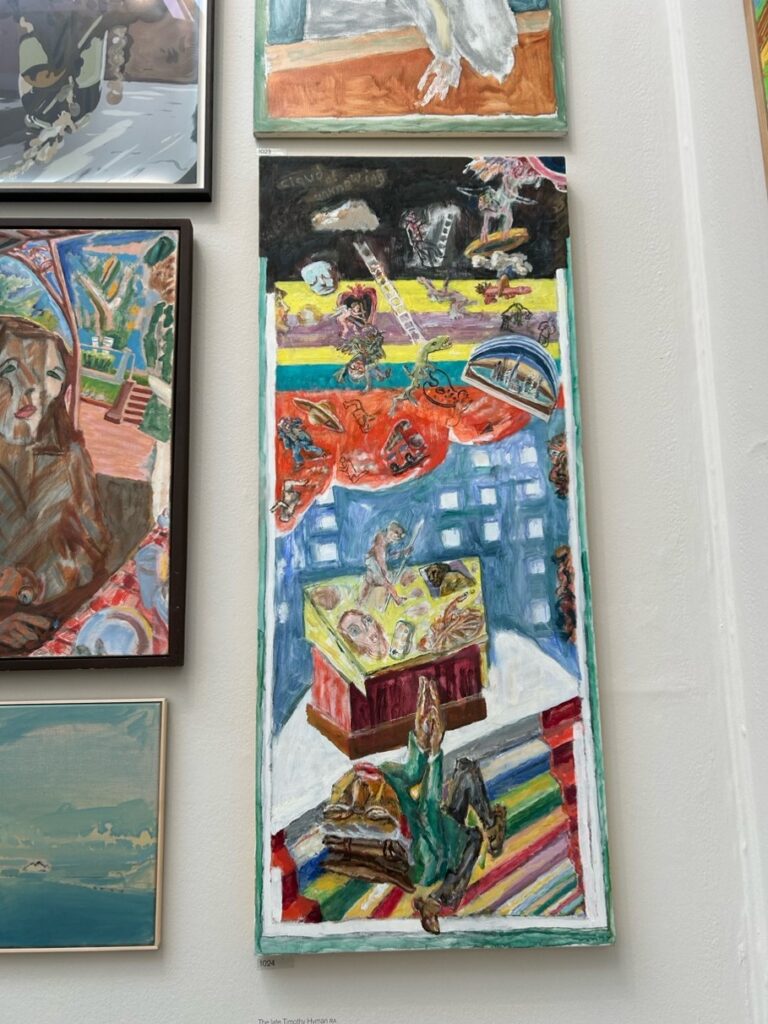

Poignantly, the late Timothy Hyman is honoured in room IV, with his work Kneeling Before the Altar of the Unknown God encouraging viewers to reflect on the limits of understanding and the necessity of acknowledging what lies beyond human grasp. This ‘unknown god’, a reference that carries biblical and existential weight, opens a dialogue not just within the artwork, but between the viewer and the ineffable, aligning with the curators’ aim to foster sensitivity toward questions of meaning and faith. Meanwhile in room III, Tamara Kostianovsky uses discarded textiles to create visceral sculptures of animal carcasses suspended on chains, which visually oscillate between beauty and brutality. These works address the violence of consumption, the scars of memory, and the cyclical nature of life and death.

Notably, her piece Growth rooted in memories of Argentinian meat markets and medical settings, merges bodily imagery with plush, reanimated materials, challenging viewers to confront both the preciousness and precarity of existence. Both present altars of their own, Hyman’s literal, Kostianovsky’s constructed from the relics of consumption and history, and each summon us to reckon with what we cannot fully know or control, be it divinity, mortality, or the ecological impact of our lives.

Ultimately, this year’s show does not promise easy answers. Instead, it embraces ambiguity and dialogue as vital forces, reminding us that in art, as in life, it is often the questions left open that carry the greatest possibility for connection and mutual understanding. The summer exhibition stands as a compelling testament to art’s enduring power to provoke dialogue, not merely through the display of works, but through inviting the viewer to engage in dynamic, living conversation that lets new perspectives emerge. Therefore, I urge you to not only see this summer exhibition but to frequent them for years to come, as each visit offers fresh insight, reminding us that art is an evolving conversation, and one that only deepens with time.

Leave a Reply